? | Home page | Tutorial | Advice and notes

Messages page # 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35

FromMe

le 13/10/2025 à 12h14

Hello.

So how can I contact LePou?

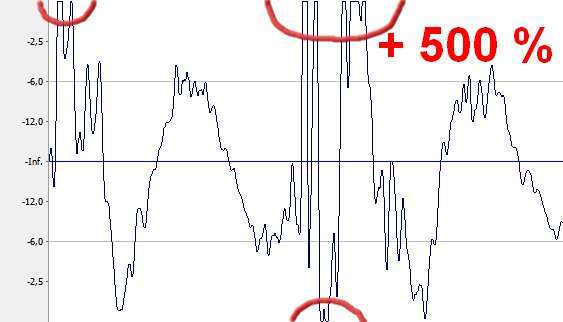

The latest X64 version of Legion has a bug where the Drive amount jumps when changing from green/red channels. The knob doesn't jump, but you can hear the drive amount jump when tweaking a little bit, so who knows what the default or chosen sound is being used whenever?

Also similar problems with the Engl as well. The old V 1.01 x86 32 bit version of Legion works perfectly however. (but the newer 64 bit version does sound a bit better, sadly).

Has you or anyone else noticed this?

I want to contact him for a way to fix these plugin bugs.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Hello,

To my knowledge, Lepou has not been active for years in the simulation community. I think he has completely given up by lack of time and motivation. So I doubt he'll be willing to fix any bugs, and I have no idea how to contact him.

Grebz

musicien-bidouilleur

le 07/09/2025 à 17h58

Juste pour t'encourager et te féliciter pour ton travail. Bonne source d'informations.

J'ai écouté en partie ta musique : il y a un monde entre 2008 et 2020, non pas concernant les titres que j'aime bien mais concernant leur réalisation. 2020 >>> 2008 à mon humble avis.

Le travail et la persévérance paient !

Bravo.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Merci beaucoup, ça me fait très plaisir !

Grebz

ace0fspades

le 25/08/2025 à 05h50

Thanks for the free impulses! Great stuff!

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Thanks for visiting!

Grebz

Jimmy

le 09/12/2021 à 15h16

Hello,

I would like to config my Schuffham S-Gear 2 but I don't know how to do.

I have Logic Pro X.6.2 with S-Gear plugin

I found your website and I ask myself what does it means in the folder Schuffham S-Gear 2.

I don't understand what you have writing like in this exemple : Guitar on the left:

1 impulse of baffle Marshall 1960A (loudspeaker: G12M) through a microphone Neumann U67 in Cap Edge position, at a distance of 2 inches (5 cm). Stereo panning: 100% left.

1 impulse of baffle Marshall 1960A (loudspeaker: G12M) through a microphone Neumann U87 in Cap Edge position, at a distance of 4 inches (10 cm). Stereo panning: 100% left.

How can I find the same sound as you ? How can I do to config my own S-Gear with these parameters ? What does it means ?

Sorry for my English ;) I’m French !

You can answer me directly on my email address.

Thanks in advance.

Jimmy

Labrava

le 29/10/2021 à 13h49

Hi Grebz,

I don't know if you read these... but I was wondering if your Lepou plugins are x32 or x64? Thanks for all the great stuff on here!

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Hello, thanks for visiting my website. They're x64.

Grebz